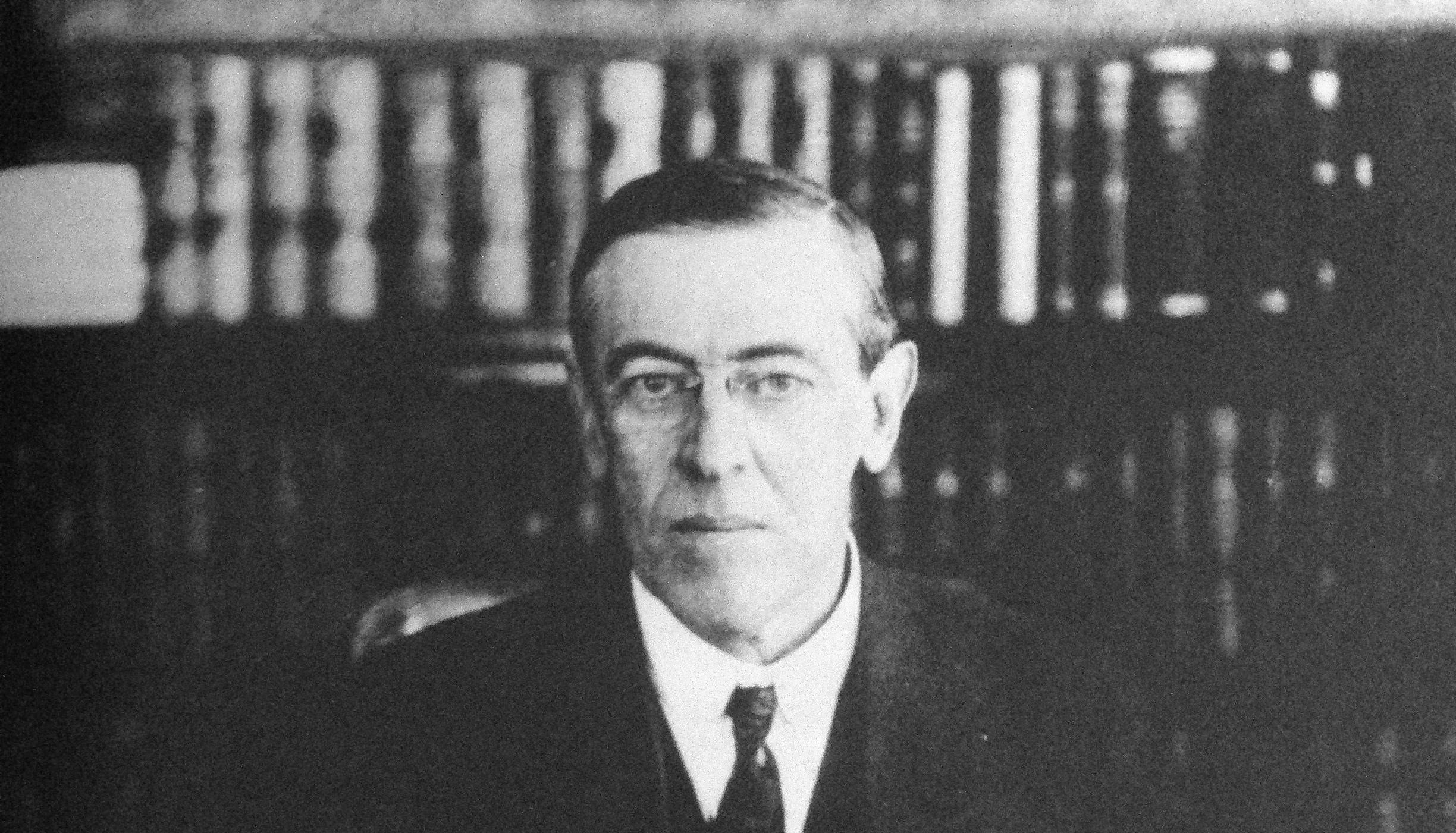

loola-games.info – Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, which spanned from 1913 to 1921, marked a defining moment in the evolution of American foreign policy. As the 28th president of the United States, Wilson redefined the nation’s role in the world and navigated the country through the global turmoil of World War I. His vision of America’s place in the world was influenced by his progressive ideals, moral diplomacy, and idealistic belief in spreading democracy. Yet, Wilson’s foreign policy was also shaped by the practical realities of international politics, the complex nature of European alliances, and the growing power of the United States on the global stage.

Wilson’s approach to foreign policy reflected a departure from the isolationist tradition that had characterized much of the 19th century. His presidency marked a shift toward more active engagement in global affairs, as he sought to assert the United States’ influence in shaping both regional and global peace. However, Wilson’s idealism was not always in sync with the challenges and complexities of international relations, and his efforts to shape a new world order were sometimes thwarted by political opposition at home and resistance from foreign powers abroad.

This article explores the evolution of Woodrow Wilson’s foreign policy, from his early principles of moral diplomacy to his involvement in World War I, the formulation of the Fourteen Points, and his efforts to create the League of Nations. It examines the challenges he faced in reconciling his ideals with the practical realities of diplomacy, and how his legacy reshaped the course of American foreign policy for generations.

Early Foundations: Wilson’s Moral Diplomacy

Moral Diplomacy: A New Approach to International Relations

When Wilson assumed office in 1913, the United States had largely adhered to an isolationist foreign policy, avoiding deep entanglements in European conflicts and limiting its role in international affairs. However, Wilson was committed to challenging this traditional approach. He rejected the realpolitik approach of previous presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, who had been willing to use military force and imperialistic tactics to protect American interests abroad.

Wilson introduced a new philosophy of foreign policy known as “moral diplomacy”. This concept was rooted in Wilson’s belief that the United States should use its power and influence in the world not for personal or economic gain, but to promote democracy, human rights, and justice. He believed that American diplomacy should be grounded in ethical principles and that the United States had a duty to promote democratic governments, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean.

One of Wilson’s earliest acts of moral diplomacy came in Mexico. When Mexican President Victoriano Huerta seized power in 1913 following a coup, Wilson refused to recognize the legitimacy of his government, calling it “a government of butchers.” Wilson sought to promote democracy in Mexico by supporting the anti-Huerta forces, leading to American involvement in the Mexican Revolution. Although Wilson was committed to promoting democratic values, his intervention in Mexico was controversial and, in some ways, reflected the complexity of Wilson’s foreign policy—his moral idealism clashed with the pragmatic realities of intervention.

Interventions in Latin America

Wilson’s policies in Latin America also saw further manifestations of moral diplomacy. In countries like Haiti and the Dominican Republic, Wilson justified military interventions as a means of stabilizing governments and promoting democracy, often citing the need to prevent European intervention in the Western Hemisphere under the Monroe Doctrine. However, these interventions were frequently viewed as imperialistic by Latin Americans, who saw them as attempts to impose U.S. control in the region.

Wilson’s administration engaged in a series of military occupations in the Caribbean and Central America, including Haiti (1915) and the Dominican Republic (1916). These interventions were aimed at maintaining stability and ensuring that U.S. interests—such as access to trade routes, resources, and maintaining political influence—were protected. Despite Wilson’s stated commitment to moral diplomacy, these actions often resulted in the suppression of local populations and the imposition of American control over sovereign nations.

Thus, while Wilson espoused a moral approach to diplomacy, his actions in Latin America revealed the limits of his idealism. Interventions in the region underscored the tension between Wilson’s professed values and the national interests that often dictated his policies.

World War I: The Shift from Neutrality to Engagement

The Neutrality Dilemma

Wilson’s foreign policy was largely defined by his initial commitment to neutrality during the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Despite the fact that European powers had plunged into a brutal conflict, Wilson believed that the United States should remain uninvolved and focus on domestic reforms. The war, for Wilson, represented a European conflict, and he argued that America’s role should be to remain neutral while continuing to trade with all sides.

However, Wilson’s position of neutrality was challenged by a number of factors. The German submarine campaign, which targeted neutral ships—including American merchant vessels—was one of the main reasons for a shift in U.S. policy. The sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, which killed 128 Americans, further inflamed American public opinion against Germany. In addition, British naval blockades of German ports affected American trade, further complicating Wilson’s stance of neutrality.

Entering the War: The Moral Justification

In April 1917, after years of attempting to mediate a peace settlement, Wilson finally asked Congress to declare war on Germany. His justification for entering the war was moral: Wilson argued that the United States needed to fight to “make the world safe for democracy.” He framed the war as a battle between autocratic and democratic nations, positioning the United States as a champion of freedom and justice on the global stage.

Wilson’s decision to enter the war was not universally popular, and many Americans, particularly those with German and Irish roots, opposed intervention. However, Wilson’s speeches and his framing of the war as a crusade for democracy garnered significant support, and he was able to rally the nation behind the cause.

The Fourteen Points: Wilson’s Vision for a Post-War World

As the war continued, Wilson sought to shape the post-war settlement through his Fourteen Points, a set of principles he outlined in January 1918. The Fourteen Points included provisions for open diplomacy, freedom of the seas, free trade, and the creation of a League of Nations that would mediate international disputes and promote collective security.

Wilson’s vision for a just and lasting peace was in stark contrast to the punitive approach that was being advocated by the European powers, particularly France and Britain. Wilson believed that the war’s aftermath should not focus on revenge or territorial gain but on establishing a framework for peace based on international cooperation and self-determination.

However, when the war ended and the Treaty of Versailles was negotiated, Wilson’s idealism collided with the realpolitik of the European powers. Although his League of Nations was included in the treaty, many of his other points, such as self-determination for various peoples, were either compromised or ignored. The treaty imposed harsh reparations on Germany, and many of Wilson’s vision for a peaceful, democratic world order was diluted by the competing interests of the victorious powers.

The League of Nations and the Battle for American Involvement

The League of Nations: Wilson’s Greatest Ambition

Wilson’s most ambitious foreign policy initiative was the creation of the League of Nations, an international organization aimed at ensuring collective security and preventing future conflicts. The League was a cornerstone of Wilson’s Fourteen Points and reflected his idealistic belief in international cooperation.

The League’s primary goal was to provide a forum for nations to resolve disputes peacefully and prevent the escalation of conflicts into full-scale wars. Wilson believed that the United States, as the world’s leading democratic power, had a responsibility to be at the center of this effort.

The Senate Rejection and the Failure of the League

Despite Wilson’s efforts to sell the League to the American public, the U.S. Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles and, by extension, American membership in the League of Nations. Senate opponents, led by Republican leaders such as Henry Cabot Lodge, argued that joining the League would entangle the United States in international conflicts and undermine its sovereignty. The Senate’s refusal to ratify the treaty was a devastating blow to Wilson’s vision and left the League without the participation of the United States, one of the world’s most powerful nations.

Wilson’s health, which had deteriorated during the war, further hampered his ability to secure support for the treaty. His failure to bring the treaty to fruition marked the beginning of a period of isolationism in U.S. foreign policy, as the country retreated from international affairs and sought to focus on domestic concerns.

The Evolution of Wilson’s Foreign Policy: A Legacy of Idealism and Realism

Woodrow Wilson’s foreign policy represented a significant shift in the United States’ approach to global diplomacy. While he entered office as an advocate of neutrality and moral diplomacy, the realities of global conflict and the rise of the United States as a global power pushed him toward a more active role on the world stage.

Wilson’s legacy in American foreign policy is marked by a tension between his idealism and the political realities he faced. His efforts to promote democracy, prevent war, and create international institutions like the League of Nations laid the groundwork for future American diplomacy. However, his idealistic vision was often challenged by the complexities of international relations, and his failure to secure U.S. participation in the League of Nations marked the limits of his influence.

Ultimately, Wilson’s foreign policy shifted American foreign relations toward a more interventionist approach, even as it remained tethered to the ideals of democracy and international cooperation. His presidency represents both the high aspirations and the contradictions of American foreign policy, and his influence is still felt in debates over U.S. involvement in global affairs.